I was a little confused and somewhat saddened to see that on the updated flag of the Swiss Guard the arms of Pope Francis were depicted with the mitre/tiara hybrid as opposed to the tiara as has always been done (even with the arms of Benedict XVI). It’s surprising because the notoriously punctilious Swiss aren’t known for accommodating whim or fashion when it comes to “their stuff”. Another thing changed for the worse.

Armigerous Saints

Monseigneur Pascal Roland

The past few days I have found myself praying for this particular bishop. It’s not that anything unusual has happened to him or that he has been particularly recommended to my prayers. In fact, I’ve never even met him. However, I find myself, lately, in the diocese of Belley-Ars in France where Mons. Roland is the bishop. So, each day at Mass I pray for him after praying for the pope. I can recall his coat of arms being discussed on one of the many heraldic fora online in which I take part. The lamb is a reference to his given name and the border of flames alludes to the new evangelization.

Herald(s) of the New King in The Netherlands

Coat of Arms of the Netherlands Royal House

From his April 30th investiture onwards, His Majesty King Willem-Alexander will fly the royal standard. His coat of arms will be identical to that used by Queen Beatrix. Contrary to the announcement in the press release of 29 January therefore, there will be no change in the design.

The blazon is: Azure, billity or, a lion rampant of the same, armed and langued gules, crowned with a coronet of two pearls between three leaves, a sword argent with hilt or, thrusted upwards, in its right hand claw seven arrows argent with heads or, tied in a garb with ribbon or, in its left hand claw. The Royal Netherlands crown resting on the ledge of the shield, supported by two lions rampant or, armed and langued gules, placed above a ribbon azure, with the motto JE MAINTIENDRAI in gold lettering. The whole placed above a royal mantling purple trimmed or, lined ermine, tied back at the corners with gold tassled cords and issuing from a domed canopy of the same, surmounted by the Royal Netherlands crown.

The royal coat of arms, which is the same as the coat of arms of the Kingdom, has only been altered once since the foundation of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. In 1907, at the instigation of Queen Wilhelmina, the number of crowns was reduced to one, surmounting the shield. At the same time, it became possible to add the royal mantle, also surmounted by a crown. The addition of other decorative elements to the coat of arms is optional.

After her abdication Queen Beatrix will adopt the coat of arms created for her (and for her sisters) in 1938 as Princess of the Netherlands, Princess of Orange-Nassau and Princess of Lippe-Biesterfeld.

Cinematic Heraldry

With the new Iron Man movie coming out soon hoards of geeks will reignite discussions of the coolest thing about Iron Man/Tony Stark. Well, the first movie already revealed the. coolest. thing. ever. In the scene showing Tony in his private jet we see on the wall behind him that TONY STARK HAS A COAT OF ARMS!!! Woo-hoo!

Rosary As An External Ornament

The rosary, or chaplet, is used in heraldry as an external ornament for those who are Professed Religious (men or women) and who are not also ordained to the priesthood. It is sometimes used by those who are officials and, therefore, entitled to use some other external ornament like a prior’s staff or even a crozier, in the case of Abbesses. The rosary is usually black and consists of five sets of ten beads, called decades, separated by five larger beads. It completely surrounds the shield and terminates at the bottom with three small beads and a cross.

The Prince and Grand Master of the Sovereign Military and Hospitaller Order of St. John of Jerusalem, Rhodes and Malta as well as professed knights of Justice of that order also make use of the rosary since they are actually Professed Religious in the Roman Catholic Church. However, they make use of a silver or white rosary that usually terminates in a Maltese cross.

Below is the coat of arms of the current Prince and Grand Master of the Order of Malta, His Most Eminent Highness, Frá Matthew Festing when he was Grand Prior of England which illustrates the use of the rosary well.

Patriarch of Venice

Since April 25 is the feast of St. Mark who is the patron saint of Venice I thought it would be nice to see the arms of that city’s patriarch, Archbishop Moraglia. Venice is one of the few (arch)dioceses in Italy that uses a kind of diocesan arms. The Patriarch’s arms always have a chief (upper third of the shield) which contains a gold winged lion of St. Mark on a silver (white) background.

Doesn’t that violate the “tincture rule” of no metal on metal? Yes, it does but sometimes you just say, “What the heck?” In the case of many ancient coats of arms the tincture “rule” which is merely a custom, doesn’t apply.

The winged lion is the symbol for the Apostle and Evangelist, St. Mark. This comes from the prophecy of Ezekial and is also reflected in the Book of Revelation. The winged lion is one of the four great creatures that pull the throne-chariot of God. These creatures came to be considered representative of the authors of the four gospels; Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. In his paws the lion holds an open book with the phrase, “Pax tibi Marce Evangelista meus” (Peace be to you, Mark, my Evangelist).

In addition to these arms of the See the Patriarch of Venice (an honorary title obtained during the days of the great Venetian Republic to add prestige to the city) uses the green galero with green cords and thirty green tassels (fifteen on either side of the shield). If the individual incumbent is created a cardinal he uses the regular scarlet galero of a cardinal. Some maintain that the galero of a Patriarch should have a skein of gold thread interwoven in the cords but this is not true. There were three popes in the 20th C. who had been Patriarch of Venice at the time of their election and all of them continues to use this chief of St. mark in their coat of arms as pope. They were: St. Pius X, Bl. John XXIII and Pope John Paul I.

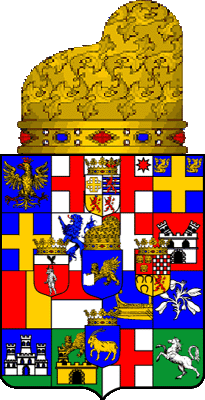

The Greater Coat of Arms of the Republic of Venice. A little busy but all their jurisdictions are in there! The patron saint of Venice is St. Mark (feast day: April 25).

Coat of Arms of the Republic of Venice, topped by the Doge’s cap. The patron saint of Venice is St. Mark (feast day: April 25).

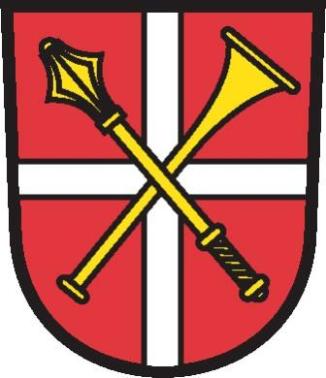

Prior’s Staff

One of the lesser known and, indeed, lesser used external ornaments in ecclesiastical heraldry is the Prior’s Staff, sometimes called the Cantor’s Staff. Like the crozier of bishops and abbots it has its origin in the staff used by pilgrims as a walking stick. As it evolved it came to be depicted as a simple staff usually of metal which terminated at the top in a small ball, or an apple, a fleur-de-lis or even the small representation of a house or chapel.

It is most often used in ecclesiastical heraldry for monastics but can also be seen in those places that still have cathedral chapters. Those officials of the chapter who do not enjoy the right to pontifical insignia, such as Priors, Provosts, Precentors or Cantors make use of it as a sign of their office. At one time Precentors or First Cantors were in charge of music for the chapter and cathedral and actually used this long staff to conduct the choir. It’s easy to see how from there it became a symbol of their office. This type of staff was also used to direct ceremonies.

Using the Prior’s Staff as a heraldic emblem was for those officials who actually used one in real life. As its use became less frequent it then evolved into an emblem for those who held the office that used to employ such staves. It is seen very little in heraldry these days.

(The example above is the coat of arms of the Collegiate Chapter of Canons of St. Vittore of Arcisate rendered beautifully by Marco Foppoli)

Sudarium

The word “sudarium” means “veil” in Latin. This veil makes an appearance in ecclesiastical heraldry in the coats of arms for abbots (see the arms of Abbot Gregory Duerr, OSB of Mt. Angel Abbey above). Since 1969 and the Papal Instruction, “Ut Sive” the use of the mitre and crozier in the coats of arms of Cardinals, Archbishops and Bishops has been discontinued. However, the mitre is still used in corporate arms for abbeys and dioceses. Similarly, the crozier is frequently used as an ornament to ensign the shield of an abbey. In some countries the mitre is still erroneously used by bishops to ensign their arms alone. While that was commonplace in the Middle Ages it is really incorrect (mind you not “unallowed” but merely “incorrect”) in modern heraldry.

While Pope Paul’s Instruction asked that the mitre and crozier be omitted from the arms of Cardinals, Archbishops and Bishops as unnecessary due to the fact that the galero with its colors and tassels and the (arch)episcopal cross are sufficient emblems for those prelates the crozier has been maintained as the external emblem particular to the arms of abbots, along with the sudarium, and of abbesses. However, to mark the crozier as the emblem of a monastic prelate it must have the sudarium attached to it.

The reason for the sudarium started out as a practical one and has, like so many other heraldic emblems, evolved into something merely symbolic. At the time when abbots were conceded the privilege of using pontifical insignia (i.e. mitre, crozier, ring) they were not originally allowed to wear pontifical gloves. The veil was attached to the crozier in order to protect the staff of the crozier from dirt and perspiration on the hands of the one holding it. Later, pontifical gloves were also conceded to abbots (and abbesses) so the sudarium became more symbolic than practical. It is also possible to find frequent examples of abbatial arms that have a crozier without the sudarium or, even, to omit the crozier entirely. This is quite incorrect.

The external ornaments proper to an prelate with the rank of abbot are the black galero with twelve tassels and the crozier placed behind the shield with the sudarium attached. Occasionally, it is possible to find the sudarium still actually used by some abbots, such as those at Heiligenkreuz in Austria. (below)

One of the Best…Ever

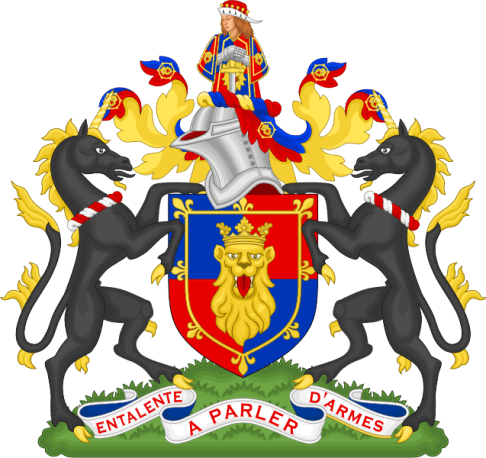

The coat of arms of His Eminence, Francis Cardinal Spellman, Archbishop of New York from 1939-1967. The blazon is: Arms impaled; in the dexter Argent on a saltire Gules between four Greek crosses Gules the sails of a windmill in saltire Argent (New York Archdiocese). In sinister Sable, on a fess Argent four ermine spots Sable; overall a bend Or goutee de sang; a chief of the Religion (Spellman).

The arms of the archdiocese employ a red X-shaped cross of St. Patrick, the patron of the archdiocese. On this is superimposed the sails of a windmill to recall the Dutch who first settled the city of New Amsterdam, later called New York. The four red crosses represent the four Gospels. Spellman’s own arms were not the first that he adopted when he was made a bishop. His original coat of arms depicted the Santa Maria, flagship of Christopher Columbus, under full sail. He used these when he was Auxiliary Bishop of Boston. After he was translated to New York Spellman adopted the arms we see here. Unfortunately, I do not know the meaning behind the ermine spots or the gold bend. I know the drops of blood were an allusion to the Precious Blood of Christ. As a Bailiff of the Order of Malta he includes both the chief of that order (Gules a cross throughout Argent) and places the shield on the cross of the order.

The external ornaments include the galero and the mitre as well as the archiepiscopal cross and the crozier. These arms were designed long before the 1969 Instruction of Pope Paul VI forbidding the use of mitre and crozier in the arms of bishops, archbishops and cardinals.

I have always like this particular coat of arms. It is an exmaple of good heraldry which is a rare find among the coats of arms of American prelates…of any era!

Musical Coats of Arms

How Many Tassels Does a Cardinal Get?

The external ornament used in heraldry that distinguishes the coat of arms of a Churchman from those of a layman more than any other is the galero. This broad-brimmed and low-crowned hat was originally a pilgrim’s hat and worn primarily when traveling in a cavalcade to shade one’s head from the sun. In heraldry it was seen as a fitting substitute for helm, mantling and crest which were considered too martial for non-combattants like clergy.

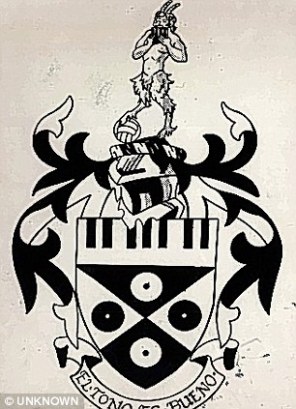

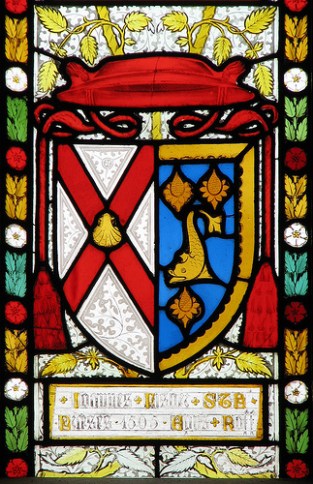

A hat originally used only in Roman heraldry and not really catching on in the rest of Europe eventually the galero came to replace the mitre in the arms of prelates since the former was seen as the more “Roman” option. The galero was first bestowed on the Cardinals of the Roman Church by Pope Innocent IV at the First Council of Lyon in 1245. It was the first hat to be distinguished by the use of a specific color (scarlet) and it was also to be adorned with tassels. However, originally the number of tassels was not fixed. There are various examples of cardinals’ coats of arms that show as few as two tassels suspended from the galero (see the arms of St. John Fisher in color below) and as many as seventy-two! (the arms in black and white above are those of Cardinal Ximenes) What marked these coats of arms as those belonging to cardinals was that the galero, cords and tassels were red and nothing else. No one else could use such a red hat except a cardinal regardless of how many tassels were suspended from it.

The number eventually was fixed at thirty (usually depicted as fifteen suspended on either side of the shield in a pyramidal pattern) only in 1832. A system for distinguishing the ranks of other clergy based on the color of the hat, of the cords and the number of the tassels did not come into existence until the Instruction of Pope St. Pius X “Inter Multiplices” in 1905.

So, all these different colored hats, cords and tassels are really a relatively recent innovation in Catholic heraldry.

Happy Birthday to Pope Benedict XVI !

Organizations for Heraldic Enthusiasts

There are numerous organizations throughout the world for those interested in heraldry. Many specialize in the heraldry of a particular country and some are simply societies for the furtherance of the appreciation and knowledge of heraldry. Some of them are private organizations (membership by invitation). Many are open for anyone to apply for membership. Here are some of my favorites. (in the interest of full disclosure I am a member of those marked with an * and also an officer in those marked with a #)

The Heraldry Society (England) *

The Heraldry Society of Scotland

The Royal Heraldry Society of Canada *

The Heraldry Society of New Zealand

The Australian Heraldry Society

The American College of Heraldry * #

The American Heraldry Society * #

The International Association of Amateur Heralds *

The Fellowship of the White Shield *

The White Lion Society (England)

The Westphalian Heraldry Society

Papal Ferula (Pastoral Staff)

There is an interesting article on the Vatican’s website about the use of the Papal Ferula (or bacculus pastoralis, (i.e. pastoral staff or “crozier”) by popes in recent decades for solemn liturgies. All those who found the return of the ultra-modern staff commissioned by Pope Paul VI (including myself who refers to it as the dental pick crozier) will find this article interesting. Apparently Pope Francis intends to alternate use between this crucifix-staff of Paul VI and the one used by Benedict XVI.

You may read the article HERE.